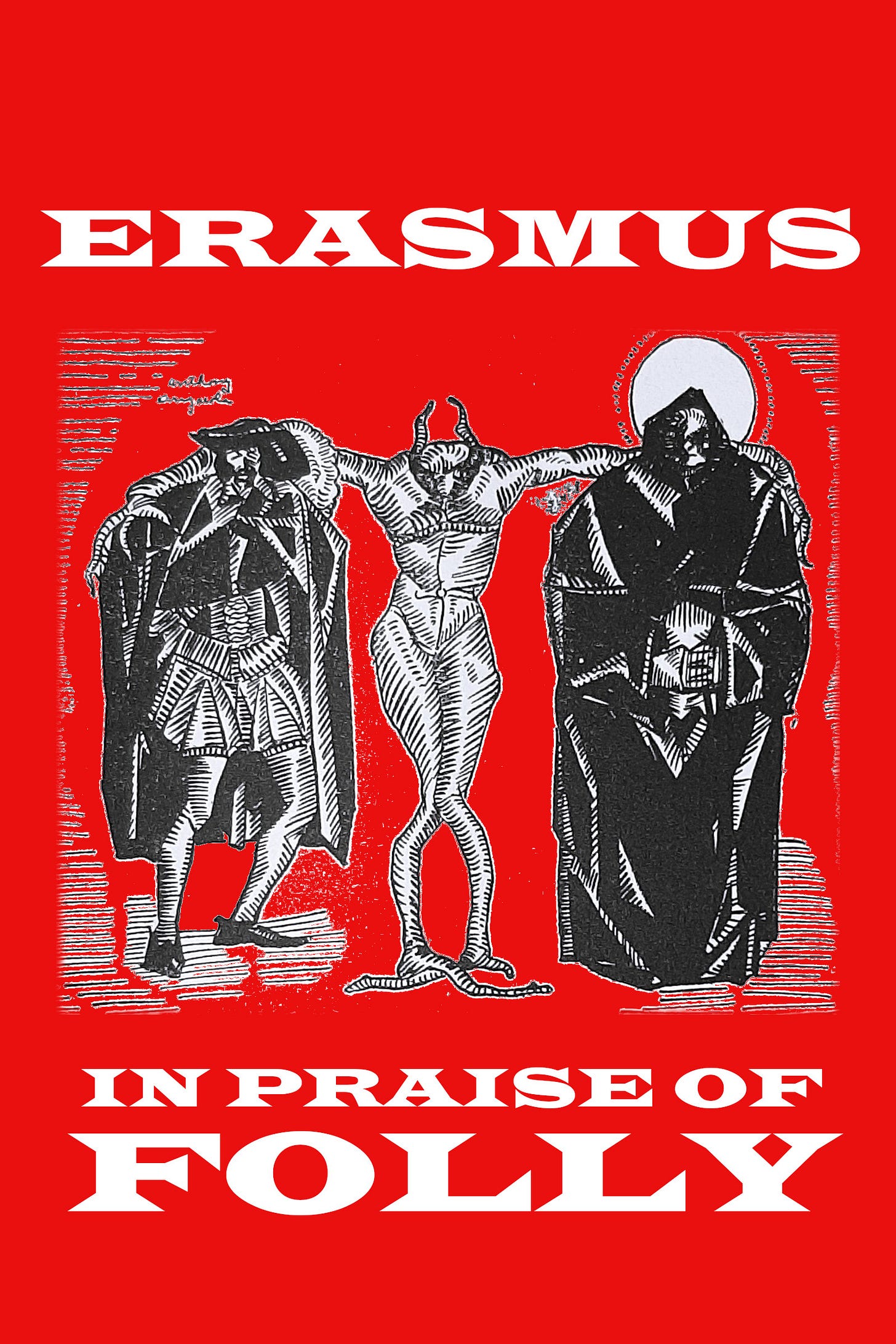

Erasmus: In Praise of Folly (Excerpt 2/5)

"Introduction in Praise of Erasmus" by Horace J. Bridges (Excerpt Two)

“Introduction in Praise of Erasmus” (Parts III - IV of X)

III

What Protestant, what rationalist, could have framed the indictment of Roman abuses more tellingly than Erasmus did, for example, in such comments as the following, taken from the Notes to his new translation (into Latin) of the New Testament? —

Men are threatened or tempted into vows of celibacy. They can have License to go with harlots, but they must not marry wives. They may keep concubines and remain priests. If they take wives they are thrown to the flames. Parents who design their children for a celibate priesthood should emasculate them in their infancy, instead of forcing them, reluctant or ignorant, into a furnace of licentiousness.

Again, annotating the text (Matt. xxiii 27) about whited sepulchres:

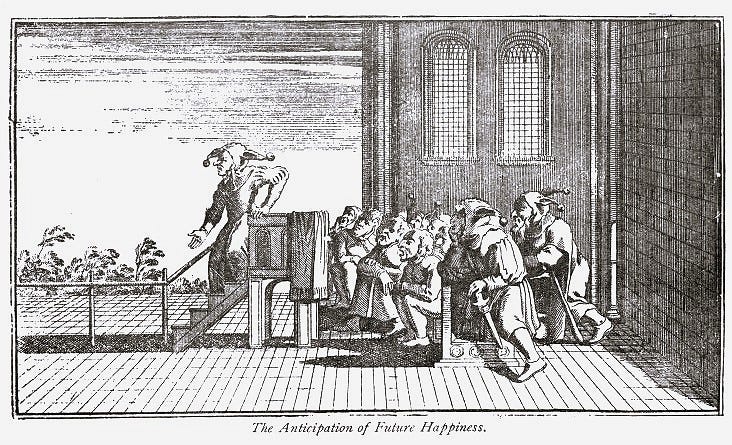

What would Jerome say, could he see the Virgin’s milk exhibited for money, with as much honour paid to it as to the consecrated body of Christ; the miraculous oil; the portions of the true Cross, enough, if they were collected, to freight a large ship? Here we have the hood of St. Francis, there Our Lady’s petticoat or St. Anne’s comb, or St. Thomas of Canterbury’s shoes: presented not as innocent aids to religion, but as the substance of religion itself — and all through the avarice of priests and the hypocrisy of monks playing on the credulity of the people. Even bishops play their parts in these fantastic shows, and approve and dwell on them in their rescripts.

Once more, as to the moral character of the pre-Reformation clergy, which is commonly believed to have been maligned by Protestant slanderers. These sentences, remember, are the work of a steady Catholic, contained in a book published with the approval of a reforming Pope and some members of the Sacred College at Rome:

Because in an age when priests were few and widely scattered, St. Paul directed that no one should be made a bishop who had been married a second time, bishops, priests, and deacons are now forbidden to marry at all. Other qualifications are laid down by St. Paul as required for a bishop’s office, a long list of them. But not one at present is held essential, except this one of abstinence from marriage. Homicide, parricide, incest, piracy, sodomy, sacrilege, — these can be got over, but marriage is fatal. There are priests now in vast numbers, enormous herds of them, seculars and regulars, and it is notorious that very few of them are chaste. The great proportion fall into lust and incest, and open profligacy.

If any reader thinks it possible to doubt this rather violent statement by Erasmus (though apparently nobody did in his own time), we might supplement it by the unconscious testimony of Sir Thomas More, who was not only a faithful son of the Roman Church, but by it is regarded as a martyr and has been beatified. Meeting Erasmus at Bruges when there on diplomatic business, More complained to him of the irksomeness of the long absence from home which such missions involved, and added, “Such an office does not suit us laymen; it is much fitter for you priests, who either have no wife and children at home, or find them wherever you go.” The constant vehemence of Erasmus on this subject was doubtless due in part to the fact of his own illegitimate birth, which itself — if the legend be true — was due to the rigid refusal of the Church to permit marriage even to men in the minor orders. Erasmus was unquestionably illegitimate; but there is grave doubt of the truth of the pretty tale about his parents which is turned to such excellent account in Reade’s great novel, ‘The Cloister and the Hearth.’

Well, we have seen how Erasmus was feeling before the Lutheran storm had broken out. Let us listen to him a dozen years after the famous struggle over indulgences, when it was already becoming clear that the stubborn refusal of all reform had cloven Western Christendom in twain. This is from a letter to a friend under date of August 13th, 1529:

What do they expect . . . who care nothing for Catholic piety, and care only to recover their old power and enjoyments? We were drunk or asleep, and God has sent these stern schoolmasters to wake us up. The rope bas been overstrained. It might have stood if they had slackened it a little, but they would rather have it break than save it by concession, The Pope is head of the Church, and as such deserves to be honoured. He stretched his authority too far, and so the first strand of the rope parted. Pardons and indulgences were tolerable within limits. Monks and commissaries filled the world with them to line their own pockets. In every church were the red boxes and the crosses and the Papal arms, and the people were forced to buy. So the second strand went. Then there was the invocation of saints. The images in churches at first served for ornaments and examples. By-and-by the walls were covered with scandalous pictures. The cult ran to idolatry; so parted a third. . . . What is more solemn than the Mass? But when stupid vagabond priests learn up two or three masses and repeat them over and over, as a cobbler makes shoes; when notorious profligates officiate at the Lord’s table and the sacredest of mysteries is sold for money this strand is almost gone too. Secret confession may be useful; but when it is employed to extort money out of the terrors of fools, when an instrument designed as medicine for the soul is made an instrument of priestly villainy, this part of the cord will not last much longer either.

Priests who are loose in their lives, and yet demand to be honoured as superior beings, have brought their order into contempt. Careless of purity, careless what they do or how they live, the monks have trusted to their wealth and numbers to crush those whom they can no longer deceive. They pretended that their clothes would work miracles, that they could bring good luck into houses and keep the devil out. How is it at present? They used to be thought gods. They are now scarcely thought honest men.

I do not say that practices good in themselves should be condemned because they are abused. But I do say that we have ourselves given the occasion. We have no right to be surprised or angry, and we ought to consider quietly how best to meet the storm. As things go now there will be no improvement, let the dice fall which way they will. The Gospellers go for anarchy; the Catholics, instead of repenting of their sins, pile superstition on superstition; while Luther’s disciples, if such they be, neglect prayers, neglect the fasts of the Church, and eat more on fast days than on common days. Papal constitutions, clerical privileges, are scorned and trampled on; and our wonderful champions of the Church do more than anyone to bring the Holy See into contempt.

Commenting on this letter, which he cites, Froude, in his Oxford Lectures on Erasmus, writes as follows: “Cardinal Newman said that Protestant tradition on the state of the Church before the Reformation is built on wholesale, unscrupulous lying. Erasmus was as true to the Holy See as Cardinal Newman himself. I do not know whether he is included among these unscrupulous liars. It is an easy way to get rid of an unpleasant witness.” Froude might have added — though perhaps he thought it superfluous, because obvious — that in such letters to his contemporaries and fellow-Churchmen Erasmus invariably assumes their consent, as to matters of notorious and indisputable fact, to his pictures of the prevalent conditions.

IV

Holding such convictions, why did not Erasmus go with the Lutheran movement? To answer this question aright is to penetrate to his secret, to grasp that view of the fundamental need of his time which made him the great man he was. Needless to say, like the other important men who had urged reform in the Church, yet declined to join the disruptive Protestants, he has had his reward in the hatred and abuse of the zealots of both sides. The monks of his own day declared that he was the cause of the whole disturbance. Luther’s revolt was laid at his door, and a hundred pulpits rang with vituperation against him, He was a Lutheran; or, rather, Luther was an Erasmian. He had been Luther’s teacher and inspirer. If now he refused to declare himself of the Lutheran party, it was only through cowardice. He had studied Greek, and urged others to study it. He had changed the text of the New Testament, instead of sticking to the good old Vulgate. Greek was the language of heresy. (So, within the past thirty years, in Italian seminaries, students have been warned not to study German, which now is the great language of heresy, as Greek was to the monkish ostriches of Erasmus’ day.) His books reeked with impieties, blasphemies, mockeries of sacred things, et cetera.

So declared his natural enemies, the monks. Of course the charge was essentially false; but it was for them the only escape from admitting the truth, — which was that their own mountainous frauds, corruptions, superstitions, ignorances, extortions, and vices were the cause which had made some such movement as Luther’s morally inevitable.

But what said Luther and his partisans? Reading the books of Erasmus, with an eye only to what they wanted to find, they not unnaturally thought that he was with them, and expected him to declare himself of their party. They were ready — nay, eager — to welcome him and accord to him the honoured position of leadership to which his learning, his genius, and his immense prestige entitled him. Their disappointment at his flat refusal to go with them was proportionate to the height and eagerness of their expectations from him. For them he was the traitor, the trimmer, the lost leader, who had abandoned what he knew to be the right cause, for ‘a handful of silver’ and ‘a riband to stick in his coat.’

The misunderstanding was perhaps to have been expected; yet to considerate observers it is clear that Erasmus had done his utmost to avoid giving reasonable excuse for it. True, he agreed with much of Luther’s criticism of current abuses — which, indeed, was little other than a paraphrase of what he had himself written; but he never for a moment desired to buy the correction of these abuses at the cost of destroying the spiritual unity of Europe and enslaving the mind of the nations in the fetters of a new dogmatism. Nothing, really, could be clearer than the warnings he gave Luther in the charming letter he wrote, in response to Luther’s advances, in May, 1519. The following is the substance of it; and our especial attention is challenged by the passages I have italicized:

My dearest Brother in Christ,

Your letter, in which you show no less your truly Christian spirit than your great abilities, was extremely acceptable to me. I have no words to tell you what a sensation your writings have caused here [Louvain]. It is impossible to eradicate from people’s minds the utterly false suspicion that I have had a hand in them, and that I am the ringleader of this ‘faction,’ as they call it.

Some thought an opportunity had been given them for extinguishing literature, for which they cherish the most deadly hatred. because they are afraid it will cloud the majesty of their divinity, which many of them prize before Christianity; and at the same time destroying myself, because they fancy I have some influence in promoting the cause of learning. The only weapons which they use are vociferation, rash assertion, tricks, detraction, and calumny; and had I not been present as a spectator — nay, had I not myself had experience of it — I should never have believed theologians could have gone to such extremes of madness. You would think it was a deadly contagion. . . . I have assured them that you were quite a stranger to me, that I have never read your books, and that I therefore neither sanction nor condemn anything you have said, I have only advised them not to bellow so fiercely in public before reading your books, but to leave the matter to those whose judgment ought to have the greatest weight; . . . but all to no purpose: such is the fury with which they carry on their ill-natured and calumnious disputes. How often have we agreed on terms of peace; how often have they, on the slightest suspicion, excited new disturbances! And these men, with such conduct as this, think themselves theologians. . .

These men have no hope of victory but in slander and deceit, and these are arts which I despise, because I rely on my own conscious rectitude. Towards you they are becoming somewhat milder; perhaps their own evil conscience leads them to fear the pens of the learned; and I would certainly paint them in their own colours, as they deserve, did not the teaching as well as the example of Christ dissuade me. Wild beasts may be tamed by kindness, but if you do good to these men it only makes them more ferocious. . .

For myself, I am keeping such powers as I have to help the cause of the revival of letters. And more, I think, is gained by politeness and moderation than by violence. . . .

Instead of holding the universities in contempt, we ought rather to endeavour to recall them to more sober studies; and regarding opinions which are too generally received to be rooted all at once from people’s minds, it is better to reason upon them with close and convincing arguments than to deal in dogmatic assertions. The violent wranglings in which some persons delight we can afford to despise, and it is useless attempting to answer them. Let us be careful not to do or say anything savouring of arrogance and tending to encourage party feeling; thus only, in my judgment, will our conduct be acceptable to the Spirit of Christ. Meantime, we must not permit our minds to be corrupted by anger, or hatred, or vainglory; for this last is an insidious enemy, and especially dangerous in the cultivation of the religious feelings. I do not, however, give you this advice because I think you need it, but in the hope that you will always go on as you have begun.

What could be kindlier or more considerate? Yet how could he, at that stage of events, have more plainly told Luther not to expect his co-operation in action destructive of the spiritual and cultural unity of the western world?

[Order Full Text to read Parts V-X]

Order Full Text

We hope you have enjoyed reading this excerpt from In Praise of Folly by Desiderius Erasmus, translated by White Kennett, edited with an Introduction by Horace J. Bridges, illustrated by Anthony Angarola, Hans Holbein, Gene Markey, and Paul L. McPharlin, with revisions and corrections by Ether Editors, published in 2023 by Ether Editions. In Praise of Folly is available from Major Online Retailers.