In Praise of Folly (Excerpt Two of Two)

You have now heard of my descent, my education, and my attendance; that I may not be taxed as presumptuous in borrowing the title of a goddess, I come now in the next place to acquaint you what obliging favours I everywhere bestow, and how largely my jurisdiction extends: for if, as one has ingenuously noted, to be a god is no other than to be a benefactor to mankind; and they have been thought deservedly deified who have invented the use of wine, corn, or any other convenience for the well-being of mortals, why may not I justly bear the van among the whole troop of gods, who in all, and toward all, exert an unparalleled bounty and beneficence?

For instance, in the first place, what can be more dear and precious than life itself? And yet for this are none beholden, save to me alone. For it is neither the spear of thoroughly-begotten Pallas, nor the buckler of cloud-gathering Jove, that multiplies and propagates mankind, but that prime father of the universe, who at a displeasing nod makes heaven itself to tremble, he (I say) must lay aside his frightful ensigns of majesty, and put away that grim aspect wherewith he makes the other gods to quake, and, stage player-like, must lay aside his usual character, if he would do that, the doing whereof he cannot refrain from, i.e., getting of children. The next place to the gods is challenged by the Stoics; but give me one as stoical as ill-nature can make him, and if I do not prevail on him to part with his beard, that bush of wisdom, (though no other ornament than what nature in more ample manner has given to goats), yet at least he shall lay by his gravity, smooth up his brow, relinquish his rigid tenets, and in despite of prejudice become sensible of some passion in wanton sport and dallying. In a word, this dictator of wisdom shall be glad to take Folly for his diversion, if ever he would arrive to the honour of a father. And why should I not tell my story out? To proceed then: is it the head, the face, the breasts, the hands, the ears, or other more comely parts, that serve for instruments of generation? I trow not, but it is that member of our body which is so odd and uncouth as can scarce be mentioned without a smile. This part, I say, is that fountain of life, from which originally spring all things in a truer sense than from the Pythagorean fount. Add to this, what man would be so silly as to run his head into the collar of a matrimonial noose, if (as wise men are wont to do) he had before-hand duly considered the inconveniences of a wedded life? Or indeed what woman would open her arms to receive the embraces of a husband, if she did but forecast the pangs of childbirth, and the plague of being a nurse? Since, then, you owe your birth to the bride-bed, and (what was preparatory to that) the solemnizing of marriage to my waiting woman Madness, you cannot but acknowledge how much you are indebted to me. Beside, those who had once dearly bought the experience of their folly, would never re-engage themselves in the same entanglement by a second match, if it were not occasioned by the forgetfulness of past dangers. And Venus herself (whatever Lucretius pretends to the contrary), cannot deny, but that without my assistance, her procreative power would prove weak and ineffectual. It was from my sportive and tickling recreation that proceeded the old crabbed philosophers, and those who now supply their stead, the mortified monks and friars; as also kings, priests, and popes, nay, the whole tribe of poetic gods, who are at last grown so numerous, as in the camp of heaven (though ne’er so spacious), to jostle for elbow room.

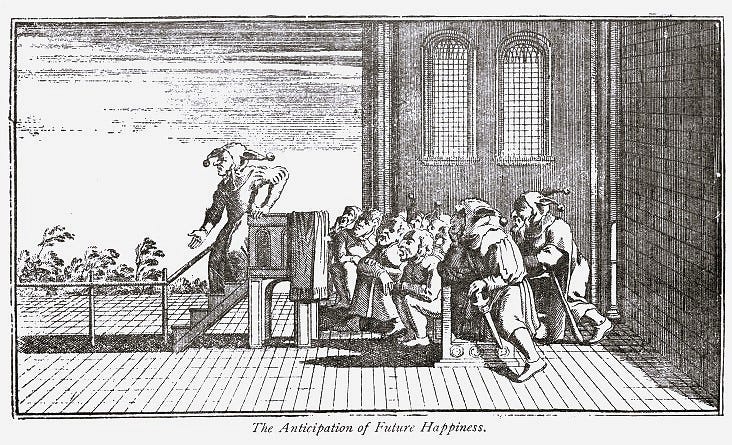

But it is not sufficient to make it appear that I am the source and origin of all life, except that I likewise show that all the benefits of life are equally at my disposal. And what are such? Why, can anyone be said properly to live to whom pleasure is denied? You will give me your assent; for there is none I know among you so wise shall I say, or so silly, as to be of a contrary opinion. The Stoics indeed contemn, and pretend to banish pleasure; but this is only a dissembling trick, and a putting the vulgar out of conceit with it, that they may more quietly engross it to themselves: but I dare them now to confess what one stage of life is not melancholy, dull, tiresome, tedious, and uneasy, unless we spice it with pleasure, that condiment of Folly. Of the truth whereof the never enough to be commended Sophocles is sufficient authority, who gives me the highest character in that sentence of his, In nihil sapiendo vita iucundissima: ‘To know nothing is the sweetest life.’

Yet abating from this, let us examine the case more narrowly. Who knows not that the first scene of infancy is far the most pleasant and delightsome? What then is it in children that makes us so kiss, hug, and play with them, and that the bloodiest enemy can scarce have the heart to hurt them; but their ingredients of innocence and Folly, of which nature out of providence did purposely compound and blend their tender infancy, that by a frank return of pleasure they might make some sort of amends for their parents’ trouble, and give in caution as it were for the discharge of a future education; the next advance from childhood is youth, and how favourably is this dealt with; how kind, courteous, and respectful are all to it? And how ready to become serviceable upon all occasions? And whence reaps it this happiness? Whence indeed, but from me only, by whose procurement it is furnished with little of wisdom, and so with the less of disquiet? And when once lads begin to grow up, and attempt to write man, their prettiness does then soon decay, their briskness flags, their humours stagnate, their jollity ceases, and their blood grows cold; and the farther they proceed in years, the more they grow backward in the enjoyment of themselves, till waspish old age comes on, a burden to itself as well as others, and that so heavy and oppressive, as none would bear the weight of, unless out of pity to their sufferings. I again intervene, and lend a helping-hand, assisting them at a dead lift, in the same method the poets feign their gods to succor dying men, by transforming them into new creatures, which I do by bringing them back, after they have one foot in the grave, to their infancy again; so as there is a great deal of truth couched in that old proverb, Bis pueri senes — ‘Once an old man, and twice a child.’ Now if anyone be curious to understand what course I take to effect this alteration, my method is this: I bring them to my well of forgetfulness, (the fountain whereof is in the Fortunate Islands, and the river Lethe in hell but a small stream of it), and when they have there filled their bellies full, and washed down care, by the virtue and operation whereof they become young again. Ay, but (say you) they merely dote, and play the fool: why yes, this is what I mean by growing young again: for what else is it to be a child than to be a fool and an idiot? It is the being such that makes that age so acceptable: for who does not esteem it somewhat ominous to see a boy endowed with the discretion of a man, and therefore for the curbing of too forward parts we have a disparaging proverb, Odi puerulum præcoci sapientia. And farther, who would keep company or have anything to do with such an old blade, as, after the wear and harrowing of so many years should yet continue of as clear a head and sound a judgment as he had at any time been in his middle-age; and therefore it is great kindness of me that old men grow fools, since it is hereby only that they are freed from such vexations as would torment them if they were more wise: they can drink briskly, bear up stoutly, and lightly pass over such infirmities, as a far stronger constitution could scarce master. Sometimes, with the old fellow in Plautus, they are brought back to their hornbook again, to learn to spell their fortune in love. Most wretched would they needs be if they had but wit enough to be sensible of their hard condition; but by my assistance, they carry off all well, and to their respective friends approve themselves good, sociable, jolly companions. Thus Homer makes aged Nestor famed for a smooth oily-tongued orator, while the delivery of Achilles was but rough, harsh, and hesitant; and the same poet elsewhere tells us of old men that sate on the walls, and spake with a great deal of flourish and elegance. And in this point indeed they surpass and outgo children, who are pretty forward in a softly, innocent prattle, but otherwise are too much tongue-tied, and want the others’ most acceptable embellishment of a perpetual talkativeness. Add to this, that old men love to be playing with children, and children delight as much in them, to verify the proverb, that Birds of a feather flock together. And indeed what difference can be discerned between them, but that the one is more furrowed with wrinkles, and has seen a little more of the world than the other? For otherwise their whitish hair, their want of teeth, their smallness of stature, their milk diet, their bald crowns, their prattling, their playing, their short memory, their heedlessness, and all their other endowments, exactly agree; and the more they advance in years, the nearer they come back to their cradle, till, like children indeed, at last they depart the world, without any remorse at the loss of life, or sense of the pangs of death.

And now let anyone compare the excellency of my metamorphosing power to that which Ovid attributes to the gods; their strange feats in some drunken passions we will omit for their credit sake, and instance only in such persons as they pretend great kindness for; these they transformed into trees, birds, insects, and sometimes serpents; but alas, their very change into somewhat else argues the destruction of what they were before; whereas I can restore the same numerical man to his pristine state of youth, health and strength; yea, what is more, if men would but so far consult their own interest, as to discard all thoughts of wisdom, and entirely resign themselves to my guidance and conduct, old age should be a paradox, and each man’s years a perpetual spring. For look how your hard plodding students, by a close sedentary confinement to their books, grow mopish, pale, and meagre, as if by a continual wrack of brains, and torture of invention, their veins were pumped dry, and their whole body squeezed sapless; whereas my followers are smooth, plump, and bucksome, and altogether as lusty as so many bacon-hogs, or sucking calves; never in their career of pleasure to be arrested with old age, if they could but keep themselves untainted from the contagiousness of wisdom, with the leprosy whereof, if at any time they are infected, it is only for prevention, lest they should otherwise have been too happy.

For a more ample confirmation of the truth of what foregoes, it is on all sides confessed, that Folly is the best preservative of youth, and the most effectual antidote against age, and it is a never-failing observation made of the people of Brabant, that, contrary to the proverb of Older and wiser, the more ancient they grow, the more fools they are; and there is not any one country, whose inhabitants enjoy themselves better, and rub through the world with more ease and quiet. To these are nearly related, as well by affinity of customs as of neighbourhood, my friends, the Hollanders: mine, I may well call them, for they stick so close and lovingly to me, that they are styled fools to a proverb, and yet scorn to be ashamed of their name.

Well, let fond mortals go now in a needless quest of some Medea, Circe, Venus, or some enchanted fountain, for a restorative of age, whereas the accurate performance of this feat lies only within the ability of my art and skill. It is I only who have the receipt of making that liquor wherewith Memnon’s daughter lengthened out the declining days of her grandfather Tithonus: it is I that am that Venus, who so far restored the languishing Phaon, as to make Sappho fall deeply in love with his beauty. Mine are those herbs, mine those charms, that not only lure back swift time, when past and gone, but what is more to be admired, clip its wings, and prevent all further flight. So then, if you will all agree to my verdict, that nothing is more desirable than the being young, nor anything more dreaded than unavoidable old age, you must needs acknowledge it as an indisputable obligation from me, for fencing off the one, and perpetuating the other.

Order Full Text

We hope you have enjoyed reading this excerpt from In Praise of Folly by Desiderius Erasmus, translated by White Kennett, edited with an Introduction by Horace J. Bridges, illustrated by Anthony Angarola, Hans Holbein, Gene Markey, and Paul L. McPharlin, with revisions and corrections by Ether Editors, published in 2023 by Ether Editions. In Praise of Folly is available from Major Online Retailers.