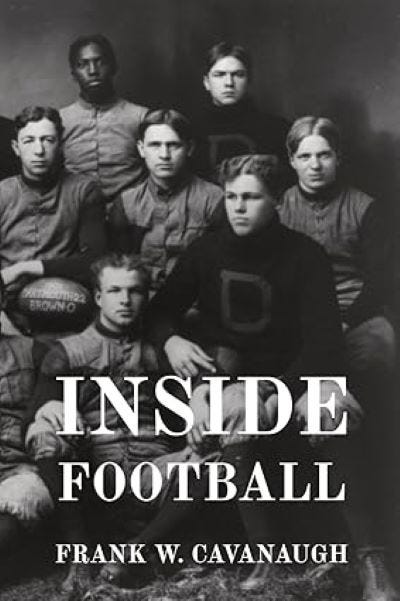

Coach Frank W. Cavanaugh

Francis William Cavanaugh was an American football coach of the old school. He was born in Worcester, Massachusetts on April 28th, 1876, to Patrick Cavanaugh and Ann O’Brien Cavanaugh, both Irish immigrants. A star football player in high school, Cavanaugh later attended Dartmouth where he continued to excel at the game. In 1898 Cavanaugh left Dartmouth to accept a job at the University of Cincinnati, the first in a series of increasingly successful coaching positions he would hold until his untimely death in 1933.

Cavanaugh’s life and career were depicted in the 1943 Hollywood film, “The Iron Major,” starring the popular 20th century Irish-American actor Pat O’Brien in the title role. Coach Frank W. Cavanaugh was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1954.

Onside Kick and Punt-Out

The onside, or quarterback, kick decidedly deserves to be included in the repertoire of a first-class team. It is a play of tremendous possibilities, with many incidental advantages accruing even when it is not successful in its main object. Not even the long forward pass gives opponents a more acute mental shock. The ball should be kicked flat, as in the case of a punt-out, with the long axis held at right angles to the kicking foot instead of in a line with the latter. A backfield jump shift to the right preferably precedes the kick, which should be directed high enough to go over the defensive halfback’s head if sent to the wide side of the field; or it may be kicked thirty-five or forty feet in the air, giving the outside backs time to get under it. Being onside they are entitled to catch the ball, even though in so doing they interfere with a catch by an opponent. They need not look up for the kick until the last moment, as the defensive halfback will indicate the spot to them. Success depends on their speed.

The ends and the left tackle, although not on side, are going down the field. They should look up and locate the ball, to cover it in case the kick is fumbled by an onside player of either team. The remainder of the line, together with the kicker, also get the direction of the ball as soon as they hear the sound of the kick and cover the danger zone to prevent a possible runback.

Figure the possibilities for yourself. In case the ball strikes the ground, you have six players of the kicking side against one of the opponents, with the defensive fullback coming up late. Viewed from any angle, this play, properly worked, gives more than fifty per cent of the chances to the kicking team, if the backfield is reasonably agile. If the ball is recovered by the kicker’s side, a touchdown is imminent. Anywhere between your own forty and your opponents’ thirty-yard line, the onside kick is a standard play.

Warning is elsewhere given against heeling a fair catch so as to prevent the catcher from taking even the two additional steps which the law allows. This applies especially to receivers of the punt-out; concerning which play a few suggestions occur. The team making a punt-out has ten men left. Four of them should cover the field; or this number may be reduced to three, if the kicker is especially accurate. The remainder should line up as near to the goal line as the rules allow; because the sooner blocking starts, the less the speed of the players scored upon, and the more effective the blocking.

This line-up should not be a scattering of players indiscriminately. If the kick is decently directed it will fall at a point somewhere in front of the goal. At any rate, so the scored-on team supposes, and it makes its charge there. The blockers should so line up as to cover approximately the width of the goal. They should not charge. Three of them would be likely, if they did, to pick the same charger. They should await the advance, each blocking the most natural man. The special punt used for this play should be practiced often. The ball is kicked flat on the instep, and dropped with its length parallel to the body, instead of at a right-angle as in punting generally. This is a very simple kick, and for short distances can be very accurately delivered.

The method of holding the ball for a try-at-goal after a touchdown or punt-out is as follows:

The holder of the ball having placed himself on the side of the kicker’s leg, preferably lies on his stomach and elbows. This position gives him absolute ease and steadiness, the knuckles of the left hand touching the ground, the lower end of the ball resting on the forefinger and middle finger spread, the end of the ball protruding slightly below the fingertips, the upper end of the ball controlled by the forefinger and middle finger of the upper hand. It may be necessary to raise the right elbow from the ground, depending on the length of the holder’s forearm. Now as the holder moves the ball to place it on the ground the fingers do not interfere in any way and have no tendency to tilt the ball when they are withdrawn. This is the most important feature. The pressure by the fingers of the right hand is only sufficient to steady the ball.

Zealous referees often annoy the kicker considerably on this play. In their anxiety that no advantage shall be given the kicking team they frequently place themselves too close to the ball. They could as readily see the ball placed and signal the defenders as promptly from a convenient distance. At the request of the kicker the referee will be very willing to retire to a position equally as good.

Order Full Text

We hope you have enjoyed this excerpt from Inside Football by Frank W. Cavanaugh, published in 2023 by Ether Editions. Inside Football is available from Major Online Retailers.