Coach Frank W. Cavanaugh

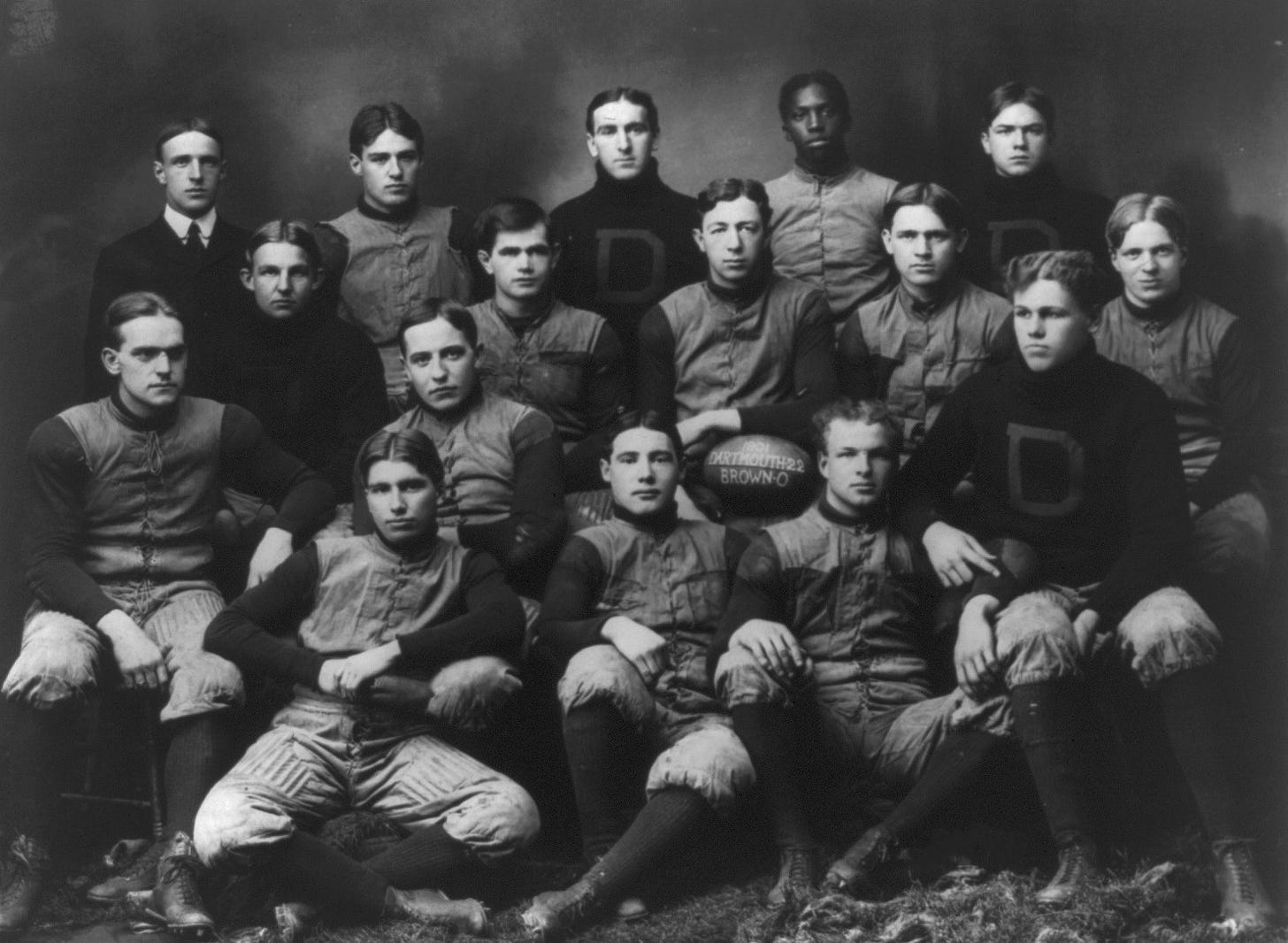

Francis William Cavanaugh was an American football coach of the old school. He was born in Worcester, Massachusetts on April 28th, 1876, to Patrick Cavanaugh and Ann O’Brien Cavanaugh, both Irish immigrants. A star football player in high school, Cavanaugh later attended Dartmouth where he continued to excel at the game. In 1898 Cavanaugh left Dartmouth to accept a job at the University of Cincinnati, the first in a series of increasingly successful coaching positions he would hold until his untimely death in 1933.

Cavanaugh’s life and career were depicted in the 1943 Hollywood film, “The Iron Major,” starring the popular 20th century Irish-American actor Pat O’Brien in the title role. Coach Frank W. Cavanaugh was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1954.

The Essence of Offense

One hallucination that many coaches and quarterbacks labor under is that in order to break the spirit of the opposing team it is well to hurl plays against the strongest man in the line; which plays, if successful, will accomplish the desired purpose. Focusing plays on the star lineman is sound policy occasionally as an experiment, or when the opposing team is breaking up and you aspire to its complete destruction; one man being seldom able to stop plays alone consistently. Under such circumstances, running down and ramming over the star lineman usually completes the rout of the opposition. But it is the extreme of absurdity to start an offense on the principle of attacking the greatest strength when both teams are fresh and neither has obtained an advantage.

There is a double risk in such a course of procedure. Not only will failure add to the assurance of the team attacked, but the same failure will give rise to serious doubts among the members of your own team as to their ability to gain. Furthermore, why is it not better on general principles to play through any man in the line rather than the strength?

Everything favors attack on the weakest man as the logical idea. A chain is no stronger than its weakest link. Even this must not be overdone. Success at the weakest point will draw help from the player on either side, which will make the going more difficult. Whereupon the quarterback should direct his plays on either side of the original weak spot. When the defending players in consequence revert to their normal positions, then attack the weak member again.

If the center is a rover it generally means that the two guards are playing a bit closer together than if he were in the line, for there is always the threat of a dash by the quarterback through center. Inasmuch as the tackles cannot draw in any closer whether the center is a rover or not, the width of territory to be defended between guards and tackles is therefore increased. Disregarding the defensive play of the center, there are the weak spots in the line. But on straight attack we may not disregard the defensive play of the center, as he is in a particularly strong position. If, however, he can be drawn to the wrong side, for example to the left side when the play is to go to the right, there is developed an extraordinary opportunity for a substantial gain. This leads to the conclusion that a delayed cross-buck, under good cover, should be a gainer. Or a feint at center, with the ball carried just outside of either guard, would, by drawing the center back into his normal position, uncover the weakness between guard and tackle.

Plays against tackle are the foundation of any scheme of offense. It must be so. Any confusion on the part of the defending team, any inefficiency by the tackle or end, opens up a beautiful opportunity. Deficiency at the guards is offset in great measure by the work of the center and tackles, backed up by the defensive quarter; but even occasional and momentary weakness at the tackles may be fatal.

The essence of the offense is to get the jump on the defensive line. This cannot be disputed as a general proposition. It would be useless to take this advantage without following it up. There is bound to be, against a strong team, an immediate defensive shock as the two lines meet. But with the advantage of the getaway there should be greater power in the offensive line at the first contact. If the attacking line merely gets the jump and expends it in the shock, stopping there, no real advantage has been gained.

The lesson is, drive while the driving is good. The legs should be brought up fast and hard, in short, jerky, powerful strides; the head set firmly in line with the spine, the muscles of the back, shoulders and neck distended. It is when one leg is raised in a long, slow effort to place it forward and continue the drive that the weakness in its owner develops, and he is hurled back or to either side by the faster-stepping, more powerful opponent. In a drive, the faster the feet hit the ground, the surer the hole.

Do not take a man out, or order it done, to the right or to the left. It is hard enough to take him out at all. All college coaches have been asked, from a hundred to a thousand times, whether the particular lineman inquiring shall take his adversary in or out. I have always answered: Never mind the direction. Take him. Get him out of the way. And, knowing where the play is going, after you get him at a disadvantage, slap him into the most harmless place.

An offensive lineman at first is in great difficulty against a standing defensive player who holds him off with his hands. This defensive player acquires the habit, after he has used the method for a short time, regardless of his specific instructions, of jumping into a powerful brace immediately after the snap of the ball, instead of a possible charge; the result is that if the play comes at him he has no time to develop a charge, and must fight it out on the scrimmage line.

If the attack is powerful, this means, at the best, stopping the play after a slight gain only. In jumping into this brace he acquires the habit, as soon as he learns the heights of his opponent’s shoulders, of shooting out both hands and arms in their most natural pose, that is, evenly. By this I mean each hand an equal distance from the ground. The offensive forward can easily develop a charge with one shoulder down. This will result in the defensive man losing one shoulder, thus throwing himself sufficiently off balance to be removed easily by his opponent.

There is another method if the offensive lineman has time; which he has on delayed bucks, intended to pierce the line at or very close to his position. This is, to make a fake charge with the shoulders, following it up immediately by the real charge. It leaves the defensive lineman stripped of his defensive power. His arms have been jammed forward and have met nothing. His poise for effective work is gone. The rest of him probably will go with his opponent’s head and shoulders.

Mix him up, get him so confused that he will lose confidence in his arms and in his defensive instructions generally, and you will soon find him down on the ground, where he belongs, but where he does not know how to work. The standing defense players stand up with equanimity in the center of the field; but most of them are found on their hands on the ground, trying to stem the tide when there is danger of being scored upon. I would much prefer to stop my opponent in the middle of the field than be compelled to do it on the ten-yard line; not so far as the thrill, but so far as the outcome of the game is concerned.

There are innumerable offensive and defensive positions that a man can be thrown into by the action of his opponent, even when the latter is being outplayed. If the play is continually stopped, however, the defensive lineman is satisfied with his defense. This is where the offensive lineman has his opportunity to put the play up to the defensive quarterback at least. He knows, at every moment throughout the play, just where the spot is, though shifting slightly from time to time, almost big or weak enough for the charging back to break through; and by a slight shift of his body at the instant when he knows the back is to strike, he can increase that opening.

Right here lies the golden opportunity. Strange as it may sound, the offensive lineman and the offensive back should have sufficiently retentive memories to store away this knowledge for future use; and surely the back should receive this information, if he does not acquire it himself, from the lineman or possibly from another back who discovers it.

So it comes down to this: in the early moments of the contest the teams are figuratively sparring for an opening. Neither may be able to accomplish much with its attack. But the team that discovers the holes a foot or two removed from the spot where the coach intended or expected them to be, will soon make the formerly impregnable line take on a decidedly different appearance.

Eyes were made for football. Do not forget your eyes, whether in the so called “blind” charge of the defensive line, as it charges with stiff neck but with forehead sufficiently turned up to enable the vision to take in all that is happening, or whether in the back as he peers into a hole or selects the correct moment for the straight arm or the arm split.

Some of the best defensive players are what might be termed “football gossips.” They have eyes and ears in the backs of their heads. They are out for information at the expense of their opponents at all times, as they should be. Coaches and players should religiously guard against giving to the opponents one iota of advance information. Watch the backs in practice every minute, and do not allow them to discover to their opponents by so much as a glance, shifting of the feet, or inclination of the body, the translation of the quarterback’s signals. It is amazing how much some defensive players can help themselves by reading aright the trivial signs and signals that denote intention and which should never be given except by an occasional clever back who gives them only to mislead.

Overdoing this deception is much to be avoided, but a back or a lineman can occasionally open a beautiful hole without physical exertion by a deceptive glance, a movement of the body or feet or a carefully worked out over-balancing of the body. And here, while we are on the subject, it is well to state that the lineman who, upon hearing the signal for a play that calls for him to open a hole, immediately responds by a shudder, a more resolute pose and a crashing of his heels into the ground, would make a better man to receive the drubbing in practice on the second team.

Order Full Text

We hope you have enjoyed this excerpt from Inside Football by Frank W. Cavanaugh, published in 2023 by Ether Editions. Inside Football is available from Major Online Retailers.